An introduction to a new scientific way of breeding better racing pigeons

Joost de Jong wrote an article in "Neerlands Postduiven Orgaan", describing in a concise way my methods of breeding. This was after my victory in de National from Chateauroux in 1985 against 8500 birds with "De Goede Jaarling". In response the staff of that pigeon paper, and myself, received several reactions to this article. I was pleasantly surprised when Jos de Zeeuw(the editor of the N.P.O.-magazine) asked me to explain my breeding methods in detail to you. I'm more than happy to grant him this request.

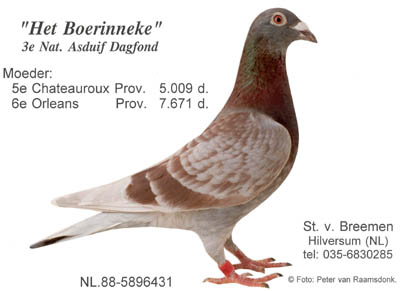

"Het Boerinneke" is a daughter of the foundation pair "Het Boerke"(heavily inbred on "De Oude Klaren '46 of Desmet-Matthijs) and "De 150 Duif"(inbred on "De 08 Duif" Janssen foundation hen). She produced a haost of winners over many generations. "Magic Mealy" her son won 3 times in the top 11 in National Dayraces and was 3rd Nat. Ace Dayraces 1994. His brother "De Vooruit" won as a yearling 5 weeks in a row the first prize. Her daughter "Gisele" too is a breeding hen in the extra category!

Before starting, however, I would like to make it clear that the sport of pigeon racing is a hobby in which we try to find some relief from our daily worries and responsibilities. There is no set of rules to tell anyone how to go about this hobby. Everyone should do what pleases him the most. It doesn't seem correct that there be laws to tell us how to get where we want to go. Never should we impose our opinions on someone else. If you would like to become a champion, however, you have to give the hobby all you've got. For this reason you should learn as much as you can about the sport of racing pigeons whenever you have the opportunity. At the same time everyone has the right to take home with him whatever he considers to be the best ideas.

My intention is not to make up a set of rules but rather to provide you with some guidelines. These guidelines were given to me by the late Professor Alfons Anker from Kaposvar, Hungary. It was he who first got me interested in his life's work: population genetics, and subsequently is responsible for these articles. I would be more honest if we put his name, rather than mine, above every article. A second point I want to bring across is concerning the terminology of the different characteristics I have made, and here I am thankful for the use of certain passages from publications of Piet de Weerd. Often they provided me with that extra understanding into the essence of certain characteristics.

Even more light was shed on these matters when I was actually holding some of the prototypes Piet de Weerd had gathered. It's fair to conclude that Professor Anker's theories, combined with the practical work done by Piet de Weerd, supplemented by my own observations, from the foundation of my own breeding methods.

Finally, it is with all the pioneering done for the pigeon sport by Prof. Anker may put those fanciers on the road to success who are interested in the genetic approach to breeding techniques. This would have given him great pleasure. It was always the wish of Prof. Anker that he solve the "flying cross word puzzle"(this was his way of describing a pigeon as well as the title of his book). By way of these articles I hope to add an extra dimension to his labors. And to you readers, I wish a pleasant time solving the puzzles, and studying.

It is my intention to arouse the readers interest in genetic breeding techniques by way of this series of articles. Many are aware that my method is based on Prof. Anker's theory of population genetics. To start with let us define the words population genetics. Population genetics is a method of breeding which, by way of rigorous selection, followed by the use of rules according to which certain characteristics are transmitted within the population, tries to acquire a population improved in quality as well as quantity.

Example. Let's assume we're dealing with a constant population of 100, now as well as later (in our case it would involve a loft of pigeons). Next, we will set a goal such as top speed fliers, but we could also take fat birds or birds with red-coloured heads. After a few years of breeding, flying, selection, you have discovered what is your best stock and you have kept these. You keep building around this stock until you have reached your target of 100 birds. Percentage wise you will now have more good birds in your flock of 100 than you had in the original group. In the past I carefully considered which routes I should follow that I should be lead to success, and I did quite well. It was at this time that I first came in contact with Prof. Anker.

When circumstances prevented me from having my own pigeons, I decided that as soon as I had the opportunity, I would start a new and would do some extensive planning. What I mean by this is that I planned to breed according to a strictly drawn concept, without allowing any, or very few exceptions. And this I felt should bring me success. At that same time Prof. Anker invited me to spend the holidays with him, and I was more than happy to accept. Together with today's most famous "fond-matador" Ton Bollebakker, I stayed at Prof. Anker's for quite a while and both of us learned a great deal.

After returning to Holland I worked my notes into a system. I was so sure I was going to be successful(half of Hungary was breeding according to Prof. Anker's theories), I confidently re-wrote my notes into a few articles. After the publication of the first article I received a very enthusiastic review by the late Arie van den Hoek, author of the "Big Pigeon Book". In the second article I was probably too over-confident in predicting that as soon as I was ready for cross-breeding an "Ace Pigeon" of exception quality would be born in my loft.

It wasn't racing the products of my theories, and a remark like that was very much resented. As a result the rest of the articles were never published. Too bad, firstly, because even now I regularly receive communications from people who have had good success using the basic ideas found in that first article. And secondly, because a few years later I not only bred one, but a number of "Ace Pigeons", in fact good enough to be mentioned in the world pigeon Guinness Book of records.

Being able to support Prof. Anker's and my own theories with solid evidence, I now will present you with an updated version of the same articles. I say updated because also in our pigeon sport there is a need for revision at certain times.

Before I present you with my breeding methods I once more will lead you through the basic steps of population genetics. I'll come back to it again and again: we first have to become familiar with the elementary principles. For most fanciers this means some persistence in reading this duller material, although I have tried to put it before you in common, every day language. It's impossible to simply it any more which means that we have to do some studying, if we like it or not.

This is the only way to get ahead in our sport. The people who's hobbies are keeping Bantam chickens, canaries or rabbits, to mention only a few, also have to study a great deal to get to the top of the ladder in their respective hobbies or sports. The same goes for the racing pigeon sport. We should not only look to standards, but rather we should repeatedly study, one by one, the different characteristics which have an influence on the flying capabilities of a racing pigeon.

When our goal is the breeding of champion pigeons, what are the distinctive characteristics which should interest us the most??

Group One:

1. Vitality.

2. Talent in certain weather.

3. Signs to come into form.

Group one:

The characteristics you find in this group are influenced by only a few genes. That rate of transmitting from parent to off-spring is small. They are the first ones to react negatively to inbreeding, but when cross-bred they show definite signs of improvement. There is a clear evidence of the so-called heterozygous in this way of breeding.

Group two:

1. "Mordant"(character).

2. Intelligence.

3. Speed.

4. Talent at a certain distance.

Group two:

In this group we find the characteristics which are influenced by the combined efforts of hundreds of genes. The characteristics, in this case are transmitted intermediary, which means that the some of the characteristics each parent contributes are evenly averaged out in the off-spring. This intermediair transmission doesn't divide itself anymore in the following generations, as it is the case with qualitative transmission. From generation to generation the quality value of these characteristics always is the average of what both parents contributed.

For example: (100+90):2=95. When we pair 95 with 100 we'll get 97,5. These are just examples. Inbreeding in this case doesn't lead to degeneration but, and this is of the greatest importance, cross-breeding in this group gives a heterose effect. The consequences of this in the breeding are as follows:

The characteristics found in group one are most successfully improved by meaningful cross combinations. This can be done by temporarily bringing in pigeons who are suitable for such crossings. The characteristics found in group two generally can't be improved by cross-breeding. Since the characteristics in this group are transmitted intermediary, the only road is rigorous selection and well planned pairings. The higher both parents rate in all these characteristics, the higher the off-spring will rate. Important here is a very old law: pairing the best with the best.

There is something else we should still mention: when we are pairing pigeons it's by far not enough to simply conclude which bird is good and which isn't. We should know WHY a pigeon is rated good, and what it's strong and weak points are.

Often the strong point in a pigeon isn't determined by it's vitality, but is found in it's keen intellect or strong character(mordant). In this case we should pair it with a partner who has plenty of vitality. But this partner at the same time should be comparable to her concerning his keen intellect and strong character. If this is not the case, we would end up with an improvement in vitality but a loss in the other two most important characteristics.

What do you have to do is evaluate separately all the different characteristics and adapt your breeding plans whenever a certain characteristic appears to be transmitted exceptionally well.

This far the theory. Next we will proceed with a more practical explanation: inbreeding with a specific purpose in mind.

Steven van Breemen

Copyright 1998. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole, in part, in any form or medium, without the express written permission of Steven van Breemen, is forbidden.

The whole book can be downloaded from "Winning Magazine" if you are a subscriber. You can subscribe here; costs 35 Euro for 1 year. You get 26 issues and have access to the archives with all previous published issues plus next to "The Art of Breeding" a second book written by me: "Hints for Mating, Breeding & Selection". A total bargain!